|

| Pascal |

|

| Nana |

Stateless in West Africa

Ten million people around the world have no nationality. In West Africa, at least 750,000 face a lifetime of broken dreams.

Lisette, 20, was born and raised in Côte d’Ivoire. To make a living, she sells grains of millet at the local market in Zuenoula. But without ID documents to prove her birthplace, or her ancestral ties to Burkina Faso, she might as well be invisible. Bereft of a nationality and many fundamental human rights, life is a constant battle.

At least 750,000 people are stateless or at risk of statelessness in West Africa. But that is just an estimate. UNHCR believes the true figure may run far higher.

Daily life for stateless people can be lonely and harrowing, and littered with obstacles. Having no ID documents means that you cannot register to go to school, open a bank account, buy property, access health services or legally marry. Being stateless means that you are more exposed to discrimination, exploitation and seclusion. In the eyes of the law, you do not exist.

A conference organised by UNHCR and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire’s economic capital, aims to prevent, reduce and ultimately eliminate statelessness in the region. The event is part of an ambitious 10-year global campaign to end statelessness.

Meet a few of the many stateless people in West Africa who have endured a lifetime of obstacles and disappointment.

Pascal

Pascal, 72, is stateless in Côte d’Ivoire. “I may be a great farmer of coffee, cocoa and rice, but not having a nationality has confined me to my village and my fields.” UNHCR/Hélène Caux

Pascal, 72, stares out over the fields of okra that he cultivates with two of his 15 children, near Saria, in central Côte d’Ivoire.

Born in Burkina Faso, he moved to Côte d’Ivoire shortly after both countries gained independence in 1960, part of the first wave of migrant labourers to work in the cocoa fields. Having never possessed a birth certificate or any form of national documentation, his only piece of identification at the time was a card from the colonial empire of French West Africa. He tried to apply for a Burkinabé consular card with it, but was told that he needed official ID.

Decades later, Pascal still has no proof of his identity and is scared to leave his village, fearing that he could be stopped and arrested. “I may be a great farmer of coffee, cocoa and rice,” he says, “but not having a nationality has confined me to my village and my fields.”

Nana

Nana, 79, was stateless for decades after moving to what is now Côte d’Ivoire in the 1940s but recently acquired a consular card from Burkina Faso. She holds a photo of her late husband.

Nana, 79, stares lovingly at the portrait of her late husband El Haj Kabré Boureima, who died in 2013. The pair moved from Burkina Faso to Saria, in central Côte d’Ivoire, in the 1940s, part of the first wave of forced labour to work in the region’s cocoa fields.

Today, over 90 per cent of Saria’s inhabitants have Burkinabé origins. Most hold either consular cards from Burkina Faso or Ivoirian documents. But this is a recent development. Until not so long ago, most people had no proof of national documentation and relied on their birth certificates, if they had one, to get around.

Without papers, many people endured discrimination during the successive political crises that rocked Côte d’Ivoire. Nana and her late husband can never reclaim those years.

Mohamed

Mohamed, 17, is afraid to leave his village because he fears being arrested or fined.

Mohamed, 17, sits in front on his house in the small village of Saria, central Côte d’Ivoire. He was born in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, to Burkinabé parents who passed away when he was very young. His mother’s older brother brought him to Côte d’Ivoire shortly after their death, and he has never returned to his birth village since settling in Saria.

He was not declared at birth and has no papers to prove his parents’ Burkinabé nationality. Now, he has resigned himself to never leaving Saria because of lack of papers.

“When I tried to travel to neighbouring towns to sell my cocoa or coffee harvests,” he says, “policemen or military stopped me and sometimes forced me to pay 10,000 West African francs [around US$ 20], which is half of my annual wages.”

Rakiata

Rakiata and her family are unable to prove their nationality. “It has been so difficult. It just feels as if we do not exist.”

Rakiata, in her mid-50s, sits with her son, daughter and grandson outside their home in Zuenoula, in central Côte d’Ivoire. Neither she nor her children have any national documentation proving their ancestral ties to Burkina Faso. As a result, they are at high risk of statelessness.

Their lack of ID has made life very difficult. Rakiata has little choice but to work as a subsistence rice farmer, because without papers she cannot join an agricultural cooperative and scale up her production. Her son, too, has repeatedly been arrested at checkpoints, detained and even beaten because he was unable to prove his nationality.

“It has been so difficult,” Rakiata says. “It just feels as if we do not exist.”

Adama

Adama, 32, says he has been arrested, detained and even beaten because he lacks papers proving his nationality.

Due to his lack of papers, Rakiata’s son, Adama, 32, has been arrested and detained on multiple occasions. He remembers one particularly memorable incident when he was traveling from Zuenoula, in central Côte d’Ivoire, to the country’s administrative capital of Yamoussoukro.

“In 2003 I was stopped at a roadblock,” he recalls. “Because I was unable to prove my identity, I had to pay 2,000 CFA [or US$ 4] and was then taken to a military camp nearby, where I was forced to clean the yard and its surroundings.”

Soldiers became impatient when they found out that Adama did not have papers proving that he was born in Côte d’Ivoire. He says they beat him before finally releasing him in exchange for some money. Even today, he is still stopped repeatedly at checkpoints on his way to the market and often forced to pay between 500 to 1,000 West Africa francs – between US$ 1 and US$ 2.

Oumarou

It took years for Oumarou, now 50, to obtain Ivoirian nationality. “I am very lucky now,” he says. “But I will not forget the years when I was recognised nowhere.”

Oumarou, 50, was born in Tenkodogo, in central Côte d’Ivoire, to Burkinabé parents. After graduating from elementary school in 1984, he tried to enrol in high school but was told he would not be accepted without a national identity card.

He went to Burkina Faso with the hope that his Burkinabé consular card would serve as sufficient proof of his nationality. There, too, he was rejected. It was not until a friend intervened on his behalf that he was able to obtain a certificate of Burkinabé nationality and continue his education.

Upon his return to Côte d’Ivoire in 1990, Oumarou applied for Ivorian citizenship, which he finally obtained five years later.

“I am very lucky now, and having Ivorian citizenship here in Côte d’Ivoire has made my life much easier,” he says. “But I will not forget the years when I was recognised nowhere.”

Abou

About, 24, is a former street child who acquired a birth certificate with help from an aid agency. UNHCR/Hélène Caux

A former street child, Abou, 24, proudly shows his Senegalese ID card. “It has been a long way for me to finally feel more at peace and safe,” he says.

Having never been declared at birth, Abou was just six years old when his family sent him to a daara [Koranic school] near Saint-Louis, in northern Senegal. But after years of mistreatment and exhausting work in agricultural fields, Abou finally escaped. He then spent years on the streets of Dakar, sleeping in the open at night and begging for money during daytime.

“I almost died of tuberculosis,” he says. “After years in the streets, I was lucky to be found by an aid agency who took care of me. They also helped me to get a late birth certificate and then ID papers.” A talented artist, Abou now gives pottery classes to young street boys.

WRITTEN BY Hélène Caux

UNHCR/Hélène Caux

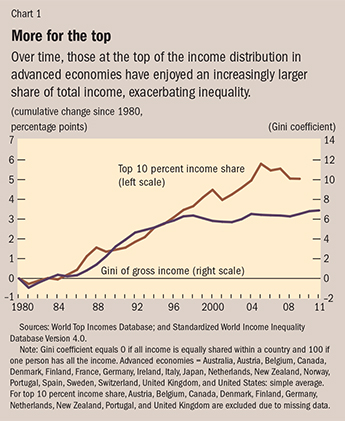

The Gini is a summary statistic that gauges the average difference

in income between any two individuals from the income distribution. It

takes the value zero if all income is equally shared within a country

and 100 (or 1) if one person has all the income.

The Gini is a summary statistic that gauges the average difference

in income between any two individuals from the income distribution. It

takes the value zero if all income is equally shared within a country

and 100 (or 1) if one person has all the income. We examine the causes of the rise in inequality and focus on the

relationship between labor market institutions and the distribution of

incomes, by analyzing the experience of advanced economies since the

early 1980s. The widely held view is that changes in unionization or the

minimum wage affect low- and middle-wage workers but are unlikely to

have a direct impact on top income earners.

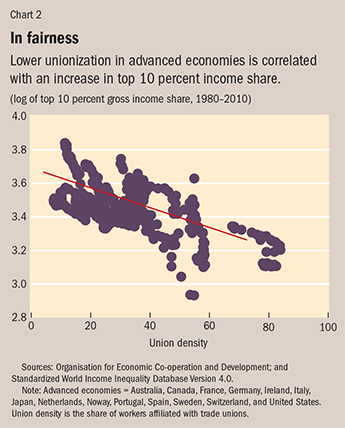

We examine the causes of the rise in inequality and focus on the

relationship between labor market institutions and the distribution of

incomes, by analyzing the experience of advanced economies since the

early 1980s. The widely held view is that changes in unionization or the

minimum wage affect low- and middle-wage workers but are unlikely to

have a direct impact on top income earners.